I saw tech become a first responder: Reflections 20 years after Katrina

Today, August 29, 2025 marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, one of the worst natural disasters of our modern consciousness. I was back in New Orleans this week, ahead of the anniversary, replaying and reimagining my experiences in a more modern context and talking with some folks who have dedicated their life to ensuring safety for others.

From a downtown view at the end of Canal Street, I’m staring across at a particular bend of the Mississippi River, toward Algiers Point. This is the city’s higher river bank and was spared the catastrophic flooding that overwhelmed pretty much anything sitting beneath.

I’m watching the slow-moving tugboats push shipping containers through the muddy traverse, navigating the sinuous arc of this mighty river, an effect that gives NOLA its same-shaped moniker, The Crescent City.

Life moves differently here.

More slowly.

People hide inside like vampires during the day because this is the hottest time of year. We are right in the middle of hurricane season. One hundred degrees and not a cloud in the sky, until there is …

The biggest storms historically come around this time, end of August, early September.

Katrina was one of those hurricanes.

Twenty years ago, I had a young family and was working as the managing editor of NOLA.com, the then website of the local paper of record, The Times Picayune (which operates today as The Times-Picayune | The New Orleans Advocate under a different ownership structure).

My job then was to get my team of digital producers out of town and figure out how to cover the storm around the clock.

This was in the beginning of my journalism career. It was 2005. Facebook was still private to Ivy League campuses, YouTube had just launched with a lot of cat videos and Twitter would not arrive until the following year.

People carried flip phones and tapped numbers three times to type a single letter. Texting was not the daily norm for most folks.

The culture was such that you still ‘dropped by’ someone's house to actually talk to them face-to-face, without a calendar appointment. And it’s still like that in many ways. Residents from all walks of life look each other in the eye, as well as strangers, and greet them, generally warmly.

This city did not feel that love back in their moment of ‘desperation.’

When Katrina first hit, most of the digital staff was evacuated and we thought maybe we’d dodged a bullet. But later Monday evening, after landfall, my editor started messaging me via AOL Instant Messenger. This was our comms platform and the real-time tech used across our displaced newsroom.

Unbeknownst to us at the moment, he would soon evacuate himself in the back of a delivery truck with the rest of the staff of the paper that was still in the city. Though some reporters had already taken to paddling through the streets in pirogues, flat-bottomed boats, made to put in nearby shallow swamps.

His last words to me were, ‘Cory, think body bags, thousands and thousands of body bags.’

Eighteen hundred lives were lost across the Gulf Coast. Not because of wind or rain, but because New Orleans is shaped like a bowl sitting below sea level and the levees broke. The city literally filled with water from the other bodies of water surrounding it. This was a human-made disaster kicked off by extreme weather that no one was prepared for, despite models that clearly showed this could and likely would manifest.

Before the storm hit, tens of thousands of people who couldn’t evacuate were encouraged into the New Orleans Superdome and the Convention Center as official shelters. Those two places became a global ground zero for the implications of the literal structural failure of the Army Corp of Engineers levee design, FEMA, government responsibility and the debate about what it means to survive a natural disaster in modern America. Especially what it means to be poor and without agency or resource.

I had evacuated to Baton Rouge with my then-partner and my kids by Saturday midday. I worked around the clock at a kind new neighbor's place who still somehow had power and decent internet. The newsroom would set up shop with LSU’s Manship School of Journalism in the coming days. We were unable to print the paper, because the printing press was, well, under water.

Everything instantly went online.

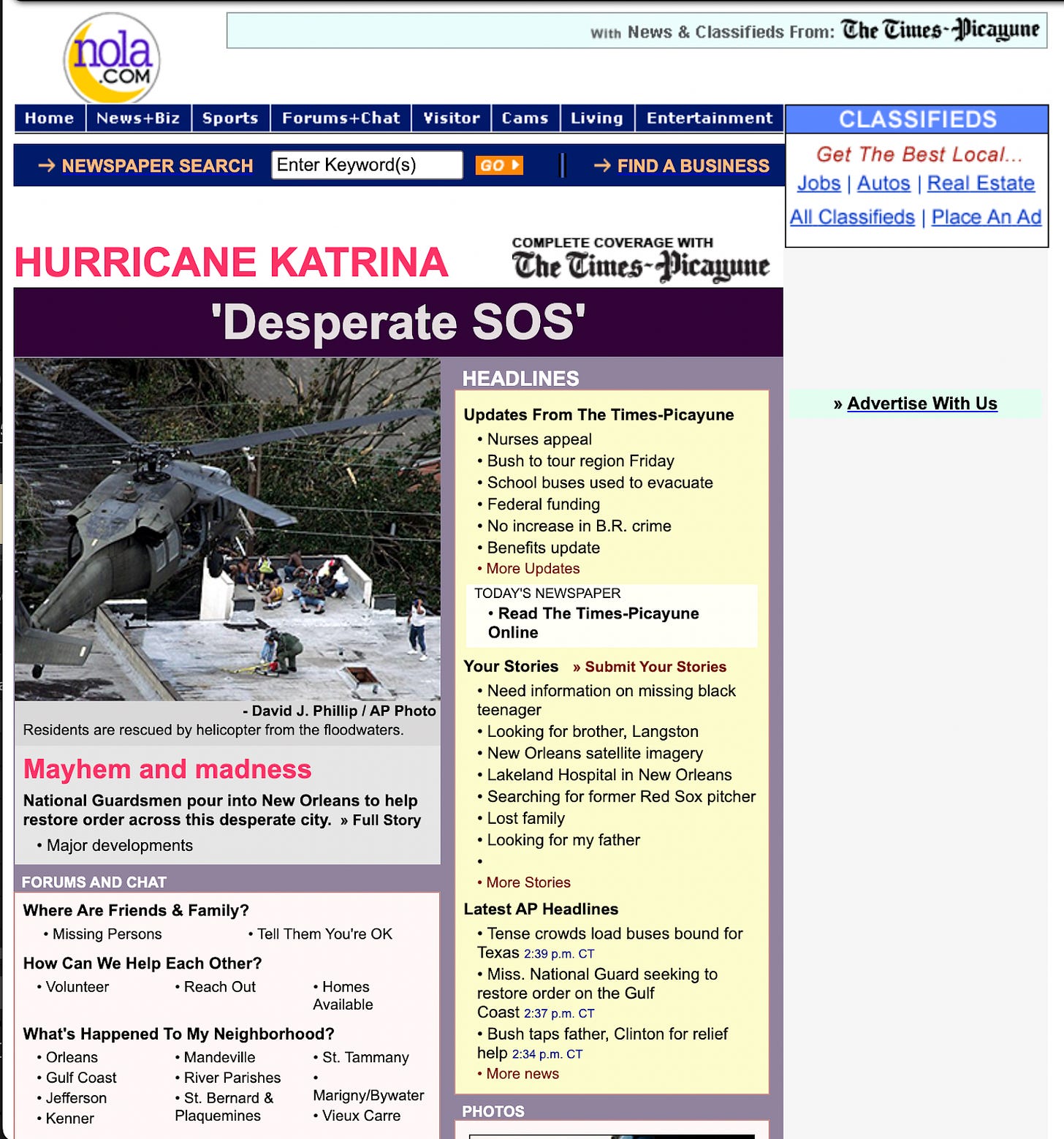

And in those early internet days, when message boards and forums still defined community, the site I helped oversee suddenly became the connective tissue for the city’s diaspora and for a national and global audience kept rapt by this unjust humanitarian crisis they could follow online.

While the city was evacuating ahead of the storm, we put up a blog, asking people to share their evacuation stories and we were curating them into our coverage.

And at first we got long tales from the interstate … ten hours to Baton Rouge (which is normally an hour drive), twenty-four hours to Houston, Atlanta, etc. But soon, these inbound stories shifted. It was a calm-before-the-storm unlike any other. Katrina made landfall, the city sustained the hit, but then the levees broke …

Our evacuation stories turned into ‘Cries For Help,’ which is what we formally renamed this blog as we started to get messages from people trapped in their attics with rising water, and who were able to get texts out from those clamshell phones to a relative or friend who then sent our ‘Cries for Help’ blog the addresses, praying someone would see them.

At first it was a trickle of a few eerie messages about rising water and loved ones left behind needing rescue, but then they started coming en masse, and we made the editorial decision to publish them all, fully unedited and with no redaction. Every minute mattered in terms of getting these details up and the more information about the circumstances and location, the better.

I had just finished working a shift of cutting and pasting, and was watching CNN when the anchor cut to a Coast Guard member in a helicopter holding up a printout of our blog — the very same Cries for Help blog I had cut and pasted into minutes before. They were using these addresses to find people.

At that moment, I knew my life’s work would be about connection, communication and content.

And here we are, 20 years later.

The storms keep coming. And they are only getting more intense and are coming more frequently. The world is just getting hotter — literally.

So now what?

From what I witnessed and where I stand today, technology is a main character in how we are going to survive, both our increasing natural disasters and in how we challenge and have any chance to beat back climate change.

Intersect episode: Community resilience and tech

That’s what I wanted to explore in this week’s episode, Twenty years after Katrina, how tech has transformed disaster response.

I sat down in New Orleans with Michelle Payne, the Chief Strategy and Resiliency Officer at the United Way of Southeast Louisiana, and Kirby Nagel, their Public Information Officer. Both women lived through Katrina in different ways.

Michelle as a college student in New Orleans at the time, Kirby as a high schooler in Arkansas whose school absorbed displaced students.

Today, their careers are dedicated to building the kinds of tools and systems we only dreamed of back then — real-time flood alerts, resilient community networks, ways to get information into people’s hands when they need it most. Especially the elderly, the poor. Our most vulnerable communities.

It was a gift to reflect with them on what it was like, what’s changed and what still hasn’t.

I found it incredibly prescient.

We were talking about tooling, about the need to meet people where they are with information and resources at a time when these kinds of disasters are happening everywhere. Think about the wildfires in California, or the floods at Camp Mystic in Texas — and that’s just in the last year, domestically.

Communities are exhausted from living through cycles of emergency, recovery and then bracing for the next one. Meanwhile government response remains uncertain and FEMA’s role going forward is somehow an even bigger question mark.

But what has evolved is technology.

Google now spins up a missing persons database any time disaster strikes. Real-time flooding alert tech is increasingly available in vulnerable areas. WhatsApp, Meta tools, social platforms — they’ve become lifelines.

We’re more connected than ever, and that connectivity is part of what is helping us to survive these disasters.

Michelle and Kirby also had some of the most practical advice I’ve heard: keep digital photos of everything, keep a running inventory, even a separate account for evacuation.

And while this episode is rooted in Katrina, it’s a reminder that this isn’t just a New Orleans story — it’s a story for literally all of us as we are living in a world reshaped by climate change, where survival depends on how we prepare, how we connect and how we take care of each other.

Tech is undeniably a huge part of that.